The winner of the Grand Prize at 2017’s YouFab Global Creative Awards is a new work of art that blends the latest innovations in 3D printing and regenerative medicine with a wholly original concept. It’s a project that’s been described as “fantastical,” “ephemeral” and a “jaw-dropping blend of art and science.”

The project, titled “Regenerative Reliquary,” is a sculpture of a jewel-like human skeleton design installed in a bioreactor that attempts to grow bone outside the body using stem cells applied to a 3D-printed framework. The piece, which creator Artist Amy Karle describes as a “relic of the future,” not only pushes the limits of fabrication and medical technology, it also raises profound questions about the future of art, design, science, religion, and even life (and death) itself.

This “relic of the future” was chosen as the winner of the Grand Prize at the YouFab Global Creative Awards 2017. While in Tokyo to accept her award, Karle sat down with Award Chairman Toshiya Fukuda to discuss how the project came together, what she’s working on now, and what the concepts behind “Regenerative Reliquary” mean for the future of humanity.

Text/Matt Schley Photos/ Hajime Kato

An Innovative Concept

Regenerative Reliquary, 2016 by Amy Karle. Photo by Charlie Nordstrom.

Fukuda: “Regenerative Reliquary” is an incredibly complex piece that’s a bit hard to wrap your head around. To start out, could I ask how you would describe it to a child, for example?

Karle: The way that I would explain it is that I’m trying to make a relic of the future. A sci-fi relic. I’m imagining a future body, and how, medically, we can heal that body—I’m working towards that vision and showing what I’ve created in the process. There’s a few sides to this: the technical side and the conceptual side.

Conceptually, what I was considering was flipping the script of relics. I grew up looking at parts of dead bodies—relics. I was raised Catholic, but I know that this is something that many religions have. I found it fascinating how these dead objects had a mystic agency to them… but it seemed backward to me, the idea of what’s really spiritual to me is life—the awe and mystery in where life comes from. There’s something in the full circle of being able to show death and celebrate life all in one piece.

So I’m exploring how to heal and enhance the body with our new technologies, but I’m also considering, on another level: if we do use these new technologies to heal and enhance us—if we can make replacement parts, and we extend our life exponentially—what will the meaning of life be? And how do we start having those conversations? If we aren’t faced with the idea of death, what does it mean to be alive?

On the technical side, basically what I tried to do is make a form that I could grow bone into—and that would only be bone afterwards, and no other material. If this was to be tested and used medically, the benefit is that it could be implanted with much lower risk of rejection, because it’s from your own genetic material. And that’s why I chose 3D printing.

Fukuda: Can you tell us a bit about the 3D-printed portion—the frame on which the cells grow?

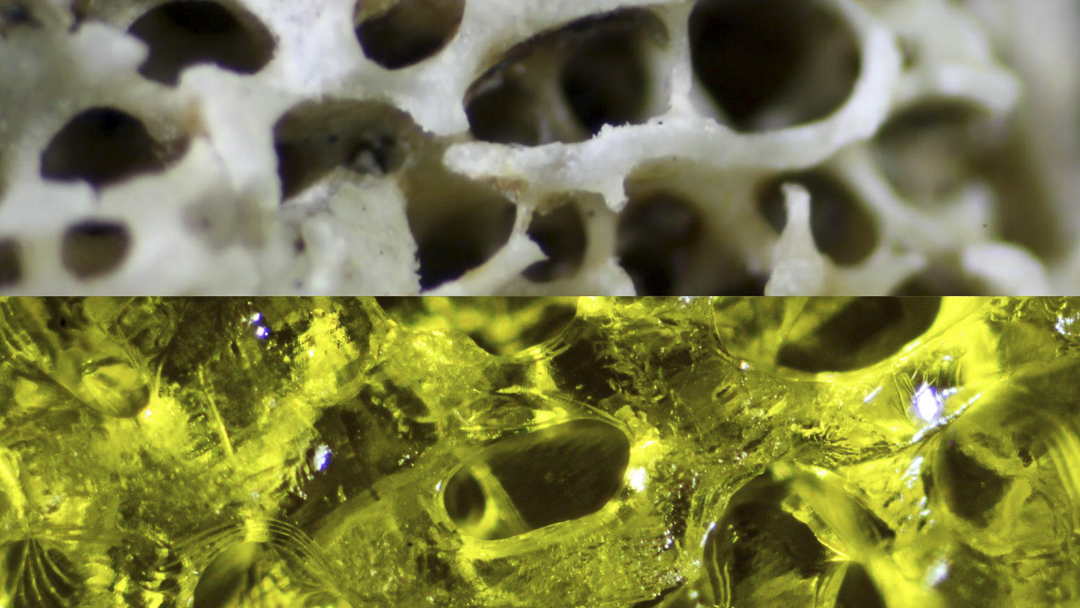

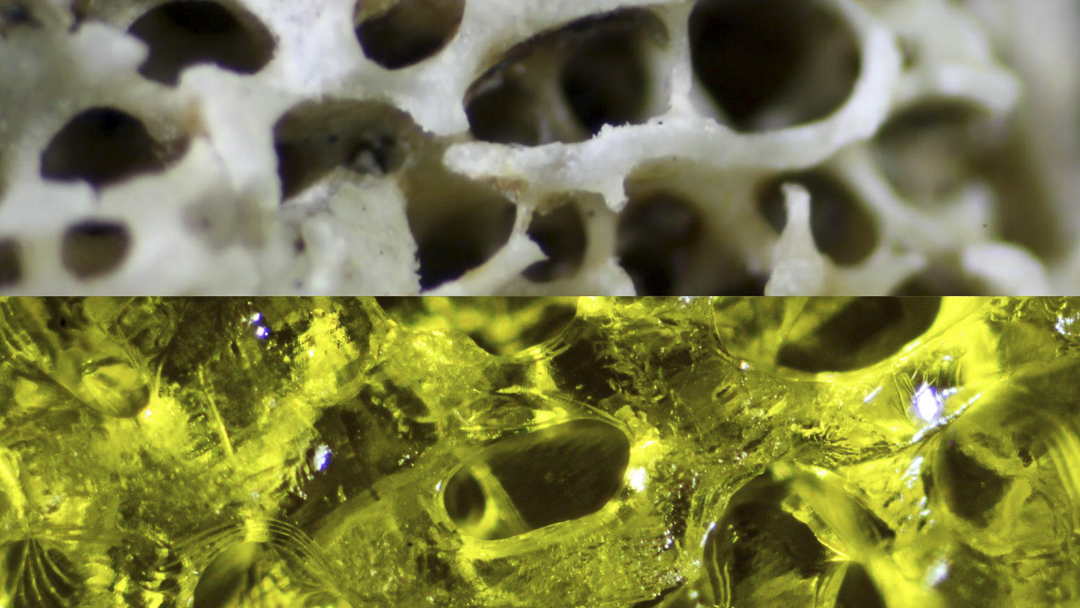

Karle: I had to create a lattice in a trabecular structure—the shape of the spongy part of bone. This shape and material properties trigger stem cells to differentiate into bone cells. The material that I’m using is a custom PEGDA hydrogel. It’s a medium that’s used regularly in the lab to grow cells. It met the requirements for the project: it had be non-toxic, it had to be something that cells would like to adhere to, and it had to be biodegradable, so that it would break down and only the cells would remain, and it had to be 3D printable. I worked with some of the best scientists and technologists in the world, and there were still a lot of failures—it was really hard just to get to the point of processing the design through the computer and developing the material to be able to 3D print with with microscopic detail.

3d print pegda trabecular scaffold for stem cell culture next to bone trabecular structure by Amy Karle

Fukuda: I understand the version you’re showing in Tokyo is an archival version, but how many of the actual units, with live cells, have you produced?

Karle: I’ve produced multiple biodegradable versions and hundreds of test squares, and stem cell culture has been done to test these theories. Some have grown-not all the way—and some have died, which are, to me, the true relics in the reliquary.

The hand design would take about two years to grow, we can’t get the cells to grow faster than they would in the human body. We don’t know what will happen with them—if cells would keep growing, if they’ll grow into form or if it will disintegrate all the way.

Life and Death, Simultaneously

Fukuda: What attracted you to working with bone?

Karle: Bones speak to me because they represent both life and death. When I was pregnant, I was thinking about how these two cells come together and make all these different forms, and their parametric and generative qualities. We tend to think of bone that’s in our body and living as rigid, but it’s not. It actually reshapes based on the forces that are put on it. I was looking at bones and thinking, “what required these bones to come into this shape, this formation?”

Feast of Eternity, 2016 by Amy Karle

The last time I really worked with bones, I was much younger, and now, looking back on it, it was around the time I was losing my mother to cancer. I can see a parallel: at that time, it was more about protection and death, and the bones that are left behind afterwards, and now that I’m a mother, it has come full circle. I think in this piece, I’m representing the cycle of life and death.

Fukuda: This concept of life and death ties into the title, “Regenerative Reliquary.”

Karle: The “Regenerative” part comes from Regenerative Medicine, and from regenerating from this base structure into a new form—the cells generating into new forms. And the relic, or reliquary, is this concept of enshrining a piece of the body that has a mystic agency to it. Not to elevate my own work as a creator, but to elevate the concept of life—and the fragility of life, too, because these are really hard to grow. Even the best scientists in stem cell research aren’t always successful and still don’t know the mystery of how life is formed.

Regenerative Reliquary, 2016 by Amy Karle. Photo by Charlie Nordstrom.

Fukuda: For us, one of the most interesting parts of this piece was the contradiction—that a traditional relic you would see in a church is dead, but the object in your reliquary is alive. It’s such a mysterious mix of life and death.

Karle: And the archival version we’re showing here in Tokyo adds another layer, because it’s a representation of that the life that was, not the actual life. It’s closer to the original meaning of a reliquary in that sense.

At the Forefront of Medicine, Tech and Art

Fukuda: This is a piece of art, but it seems like there’s huge potential for medicine as well using these methods.

Karle: Yes, there’s huge potential. Metal implants are already being made in a similar workflow, however, there are problems with introducing a foreign material into the body. If we can create bone grafts in this method then a patient’s own stem cells can be used to create a custom graft. This would reduce time on the operating table and lower the risk for rejection since no foreign material would be introduced to the body. It would also have the potential to continue to grow with the body.

Fukuda:What about on the digital side of things?

Karle: One recent advancement is neural networking and machine learning. For example, doctors can now input scans—say, for example, heart scans. Big data can compare 10,000 healthy heart scans to a patient’s heart that has some problems or deformities, and the computer can help diagnose things that the doctor doesn’t see.

Now, there are many things the technology can’t assist with—real live doctors have intuition, kinesthetic intelligence—but there are some ways that the technology can exceed what we can do as humans, so that we can work side by side for best results.

A next step that I plan with my work is being able to take that diagnosis and use generative programs to design what a healthy heart would look like and then bio-print it.

The big picture is that medicine and science is making rapid advancements from the technology—there’s a lot of pros for using it. But I’m also concerned about this unchecked proliferation. It’s important to take the long view and think things through, and I don’t hear enough of that being done. I’m very concerned about using technology conscientiously for our best and highest good. Technology can be used for our demise, or it can lead us towards an enlightened singularity. It really depends on how we choose to use it.

Fukuda: We’ve talked about the potential in terms of science, but what about in terms of art and design?

Karle: I was thinking: “if I’m going to be growing cells outside the body, what is smart to grow?” I’m not sure what the answer is yet, but this piece is working towards that idea. In art and design, we no longer have to start with something that is inanimate and subtract. We can now do things that are additive, adding layers over time like in nature. This project is an exploration of additive manufacturing and learning from how nature forms and creates.

The question is: using the very building blocks of life, what can we grow? And I think this project is just the very tip of the iceberg in what we’ll be able to do in terms of growing forms. The concept “how can we make art that grows?” is extremely interesting, and it has implications for industrial design too. How can we make buildings that grow? How can we make substrates that grow?

Success / Next Steps

Fukuda: This was such a complex piece, with so many things that needed to go right for it to succeed. Was there any point where you thought it might not work?

Karle: Just about every day (laughs). But, you know, this is part of what’s exciting about collaborating. I feel like when you have a good idea it’s like a magnet, and it draws the right people to you. I’m an artist and I can’t make these kinds of projects alone. That means I have to get the right people excited about working on the idea, and it has to be worth pursuing on many fronts—art, design, technology, science. If the right people—the right experts—that believe in it and are willing to contribute, it brings an energy, a belief that we can do this seemingly impossible thing, and amazing things happen in that space.

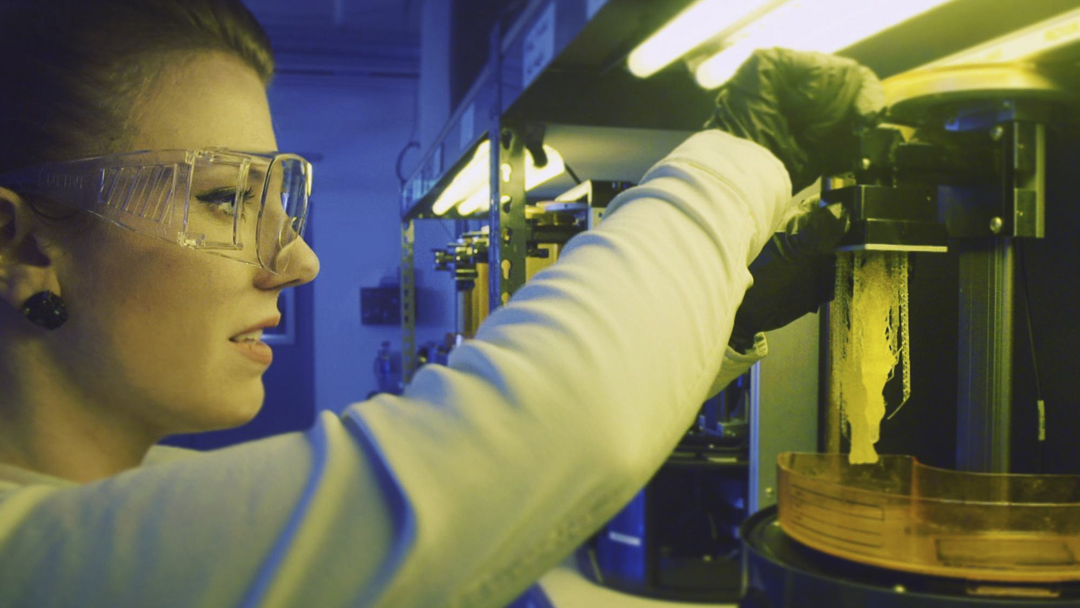

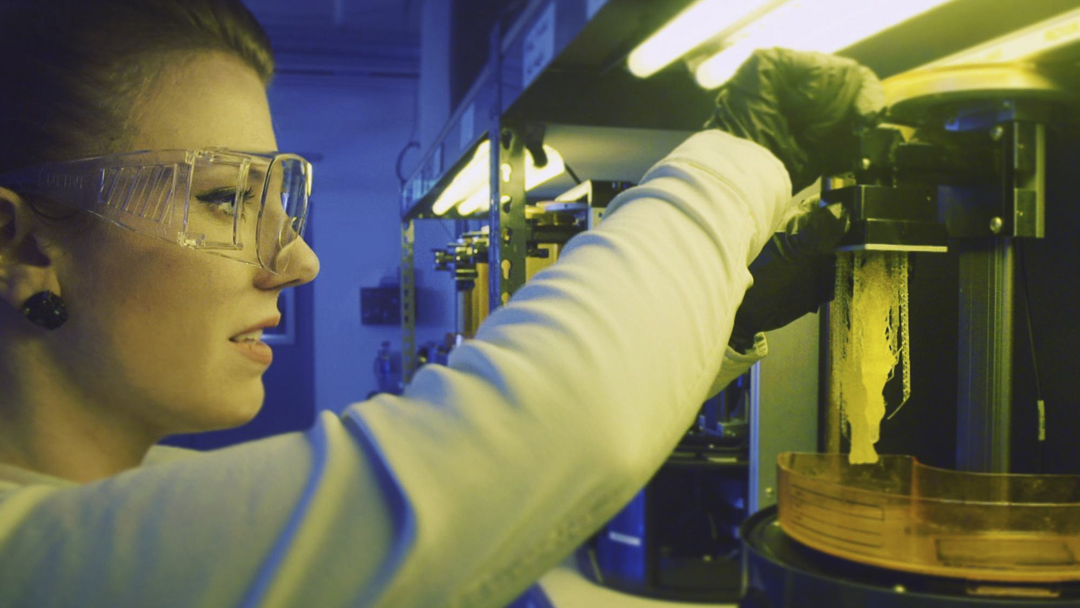

Artist Amy Karle 3d printing bioprinting

Fukuda: What are you working on now?

Karle: What I’m exploring now is using machine learning and neural networking to propose solutions for our bodies, and I’m articulating it through 2D and 3D art and science. My goal is to be able to scan anatomy in 3D and understand parts of our body, and how our body functions and works—and then through a machine learning system, have generative designs be proposed in 3D form, which I would then display through sculpture. Now, this is really difficult—we can’t do it in 3D yet—but we can do it in 2D, so I’ve started there.

The Wisdom of the Heart, 2017 by Amy Karle, made via artificial neural networking and by hand

As a example, how I work as an artist is: I go to an institution like the California Academy of Science and pull 10 bones that I think are really beautiful or really interesting, and then I make a sculpture or drawing of a new bone that’s inspired by these bones—something that is similar, but is also new.

With the computer, I’m trying to train a whole software hardware system to do something like this, to think like I think as an artist, and follow my workflow, adding more AI and automation into the process. The system I use now is very laborious, but a lot of that process could be automated, once I train the system to think like I do as an artist and apply my style to the input data.

Fukuda: It sounds like you’re basically teaching the computer to be another you.

Karle: Yes. I’m using artificial intelligence as a supportive artificial imagination to help expedite the prototyping process and work faster. It’s not the be-all end-all, but it’s another tool I can use as an artist. And through building these neural networks, we learn more about what it means to be creative, and how our brains work.